Learn about Longevity

Navigating health span and life span

“The starting point for NEM was the realization that the Swedish healthcare system needs to change in order to meet the demands of an aging population. We saw a solution to improve healthcare and adapt it to the requirements of the future. But to understand how we got here, and why longevity medicine is so important, we first need to understand how healthcare is evolving and the needs driving that development.”

Estimates suggest that in the pre-modern world, life expectancy was around 30 years (1). In the early 19th century, life expectancy increased in industrialized countries due to better health care and hygiene, healthier lifestyles, sufficient food, and reduced child mortality. Today, life expectancy has been increasing worldwide. Global life expectancy has increased by more than four decades since the 1880s and more than doubled since the 1900s. The average global life expectancy was 73.4 years in 2019 (2).

Life expectancy: A statistical measure that represents the average number of years a population (a group of people) is expected to live based on current mortality rates (average age of death in a population).

The global population is at its peak

The global population has tripled since 1950, reaching 7.8 billion in 2020 (4). With the increase in global life expectancy, the population of people aged 70 and above has increased sixfold since 1950.

The difference between life expectancy, life span, and health span

Life expectancy is a statistical measure representing the average number of years a group of people, typically a population, is expected to live based on current mortality rates (1).

Lifespan is the total number of years lived by an individual (4).

Maximum lifespan refers to the maximum or potential length of time that a living organism, including humans, can live under optimal conditions (4).

Health span is another critical concept. It is the period of life before the onset of chronic disease and disabilities of aging, i.e., life spent in good health (6).

The average global life expectancy was 73 years, but the maximum life span is 120 years.

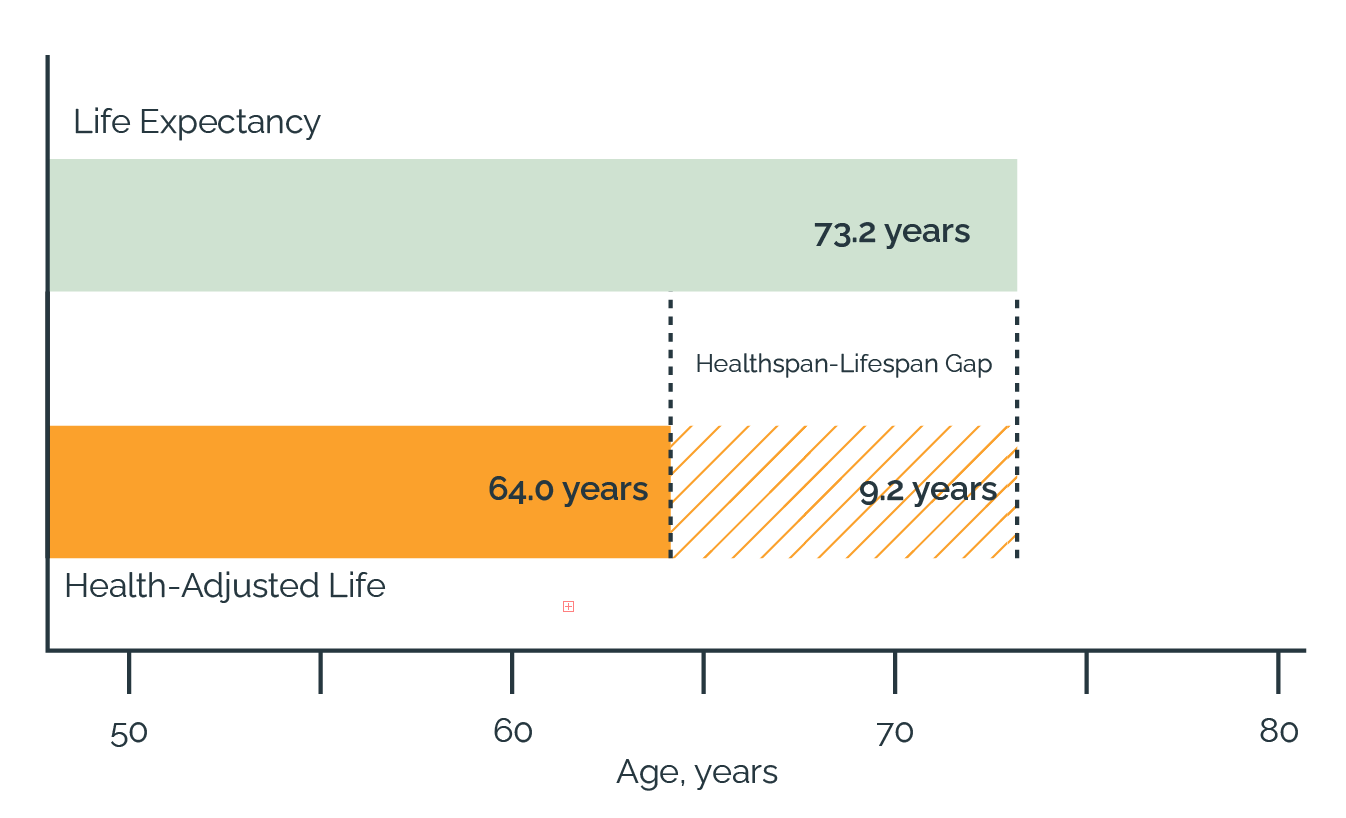

A growing gap between longer life and good health

Our lifespan, the number of years we live, does not tell us anything about the number of years we spend in good health.

Scientists have developed a metric called “health-adjusted life expectancy,” which provides a more comprehensive understanding of our overall health (on a population level) compared to the years we live. The current health-adjusted life expectancy is 64 years.

So, if we think about life expectancy as a population-level measure of a lifespan, we can think of health-adjusted life expectancy as a population-level measure of health span (4). In other words, lifespan is the total number of years an individual lives. Health span is the number of years that an individual is disease-free. That means that although we may live on average 73 years, we are healthy for 64 years (4). This leads to a 9-year gap that we spend in poor health, usually with chronic diseases, and decreased quality of life.

This gap is called the “health span–lifespan gap.”

“While years are being added to our lives, life is not being added to our years: the extra years are being added at the very end of our lives and are of poor quality.”(7)

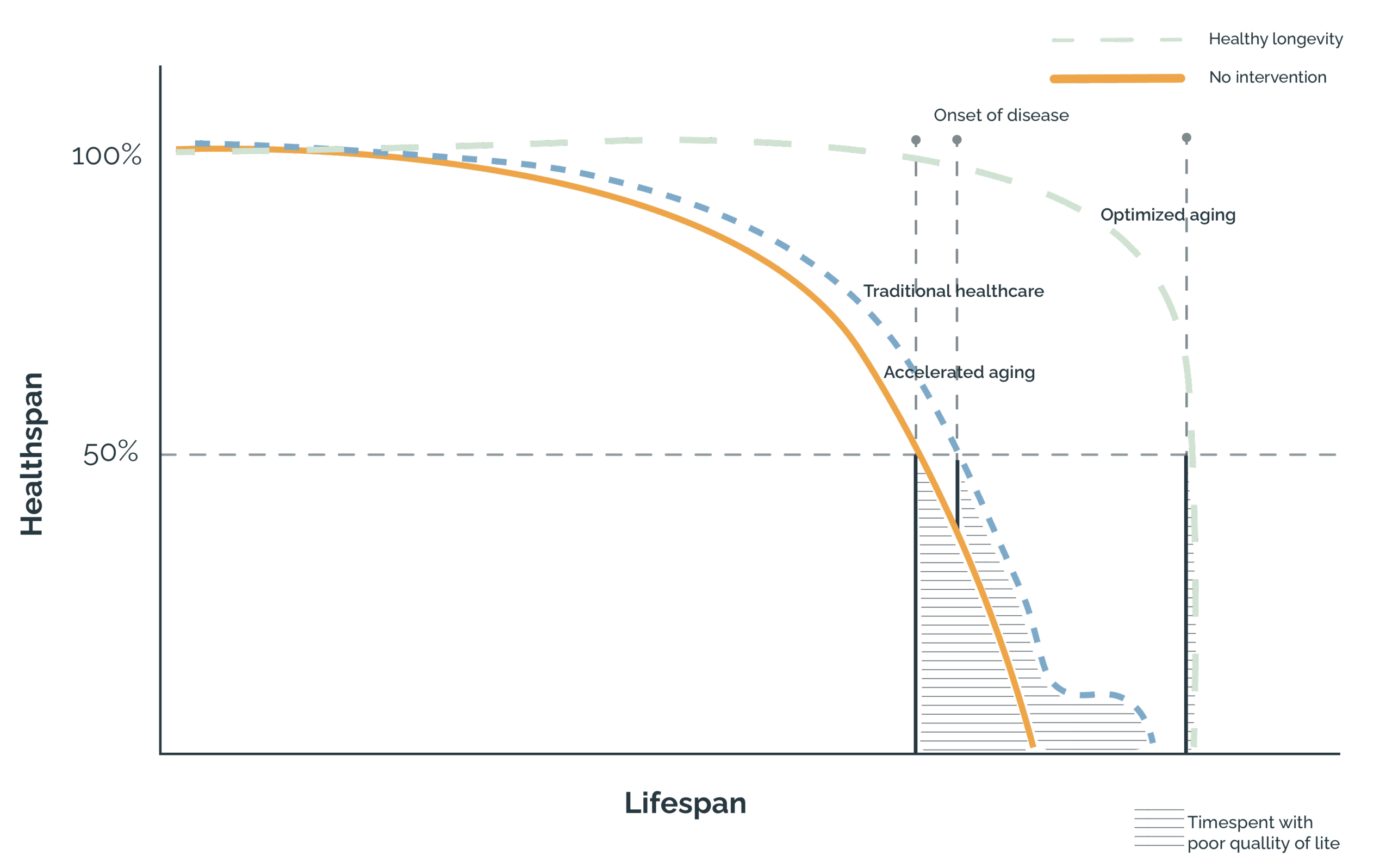

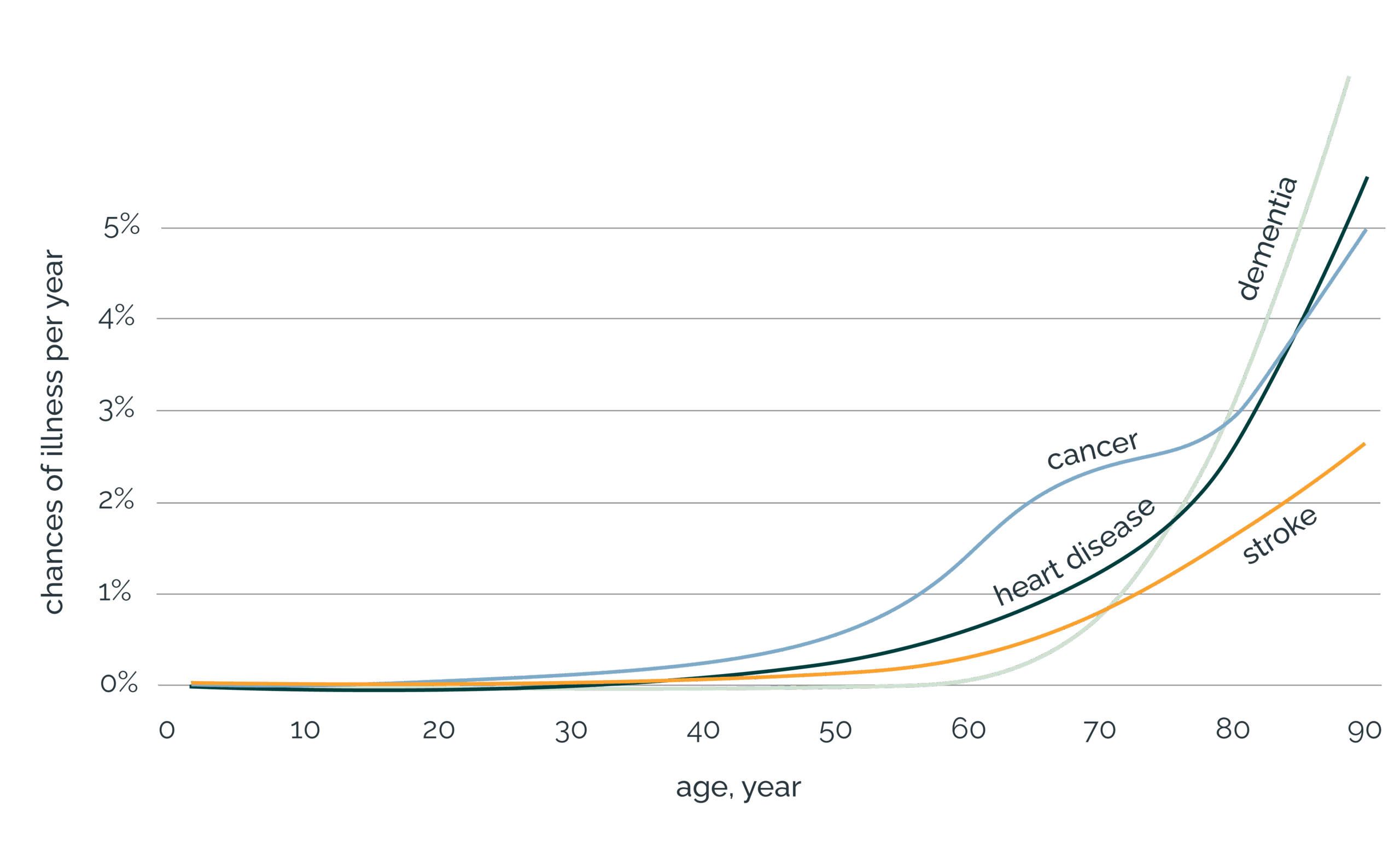

To decrease the gap, we must understand the main diseases that make us sick when we age. We need to understand what causes them and how to prevent them.

Age is one of the leading risk factors for chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cognitive disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (4). Among those, four common conditions – cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases- account for 80% of chronic disease-related deaths (8). Additionally, aging is associated with frailty, a multisystem decline characterized by increased vulnerability (4).

So, the question arises:

The complex relationship between aging mechanisms and chronic diseases resembles the chicken-and-egg scenario. Despite extensive research, there’s currently no specific treatment for aging. Focusing on known risk factors and intervening in chronic diseases may indirectly influence shared mechanisms with aging.

Waiting until the chronic disease develops is not an option.

In today’s society of instant gratification, who wants to start working on something today only to see the direct benefits when they are older? The thing is that if you start working on preventing the most common chronic diseases, you will feel better already today. You will become more fit, have more energy, sleep better, and the list goes on.

That setup led to significant developments of vaccines and antibiotics and resulted in improved lifespan. However, as societies have evolved and lifestyles changed, non-infections chronic diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease, have become a primary public concern.

We go to the doctor when something hurts, which is usually a sign that a condition has already developed. There are public health prevention efforts such as vaccines, screening for different types of cancer, and awareness campaigns. However, they are not enough to compress the life span-health span gap.

Contemporary medicine largely ignores the fact that no two individuals are identical in terms of their genetic or epigenetic build-up, ethnicity, lifestyle, etc. (9). There is no single solution or medication for the entire population. At NEM, we understand that every person is unique. What works for one individual may not work for another, which is why we always take a personalized approach to your health.

By interpreting clinical findings and biometric data, your personal physician creates a tailored Action Plan with recommendations on nutrition, sleep, supplements, exercise, and lifestyle changes. Together with regular check-ups and blood testing, you build new and sustainable habits for a healthier and longer life.

References

- Roser M, Ortiz-Ospina E, Ritchie H. Life Expectancy. Our World Data [Internet]. 2013 May 23 [cited 2023 Nov 7]; Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

- GHE: Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy

- Center PR. Chapter 4. Population Change in the U.S. and the World from 1950 to 2050 [Internet]. Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. 2014 [cited 2023 Nov 7]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2014/01/30/chapter-4-population-change-in-the-u-s-and-the-world-from-1950-to-2050/

- Garmany A, Yamada S, Terzic A. Longevity leap: mind the healthspan gap. NPJ Regen Med. 2021 Sep 23;6:57.

- Kaeberlein M. How healthy is the healthspan concept? GeroScience. 2018 Aug 1;40(4):361–4.

- Moqri M, Herzog C, Poganik JR, Biomarkers of Aging Consortium, Justice J, Belsky DW, et al. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell. 2023 Aug 31;186(18):3758–75.

- Brown GC. Living too long. EMBO Rep. 2015 Feb;16(2):137–41.

- Bennett JE, Stevens GA, Mathers CD, Bonita R, Rehm J, Kruk M, et al. NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. 1088 [Internet]. 2018 Sep 22 [cited 2023 Nov 24]; Available from: http://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/63328

- Carbonara K, MacNeil AJ, O’Leary DD, Coorssen JR. Profit versus Quality: The Enigma of Scientific Wellness. J Pers Med. 2022 Jan 3;12(1):34.