The effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance

The effect of the menstrual cycle (MC) on exercise is a topic attracting attention from professional athletes and people in general. Performance during exercise is believed to be impacted by the fluctuating levels of female sex hormones. However, researchers in the field of sports medicine are currently trying to understand the connection between MS and athletic performance (1). Indeed, a recent article highlighted the need for researching the effects of the MC on female athletes and their performance and recognized that a gap in knowledge exists (1). Although it has been reported that over 41 % of exercising people believe that their period has a negative impact on exercise training and performance, due to the scarcity of sports research in women, explanations for this are lacking (1). That is caused by a significant underrepresentation of women included in sports clinical studies, and clinical studies in general.

As the investigation of the MC on exercise is a relatively new field and not much conclusive research is available, no guidelines can be issued at this time. However, most menstruating people have symptoms during the MC. So, how can people cope with their symptoms in a way to optimize performance, decrease injuries and improve their well-being?

Basics of MC – What is a menstrual cycle?

The MC is an important cyclical biological process where large cyclic fluctuations in sex hormones, such as oestrogen and progesterone, are observed (2). Through these fluctuations, the body is prepared for pregnancy each month. The MC starts on the first day of the menstrual period and lasts until the first day of the next menstrual period. Each cycle is on average 28 days, but this is highly individual. Below is a general discussion for people assigned females at birth with 28 days regular MC. Even though some people may have longer or shorter MC the phases are the same for everyone.

The phases of an ideal menstrual cycle

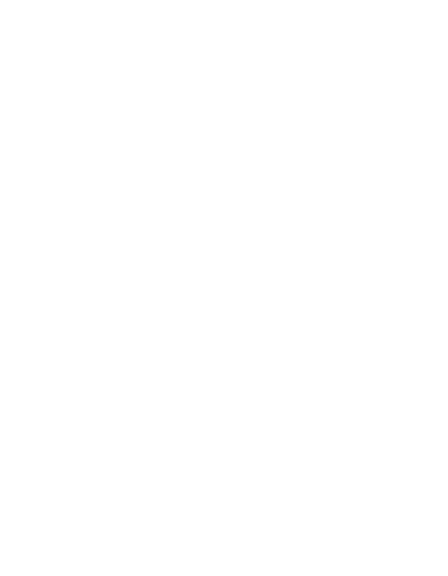

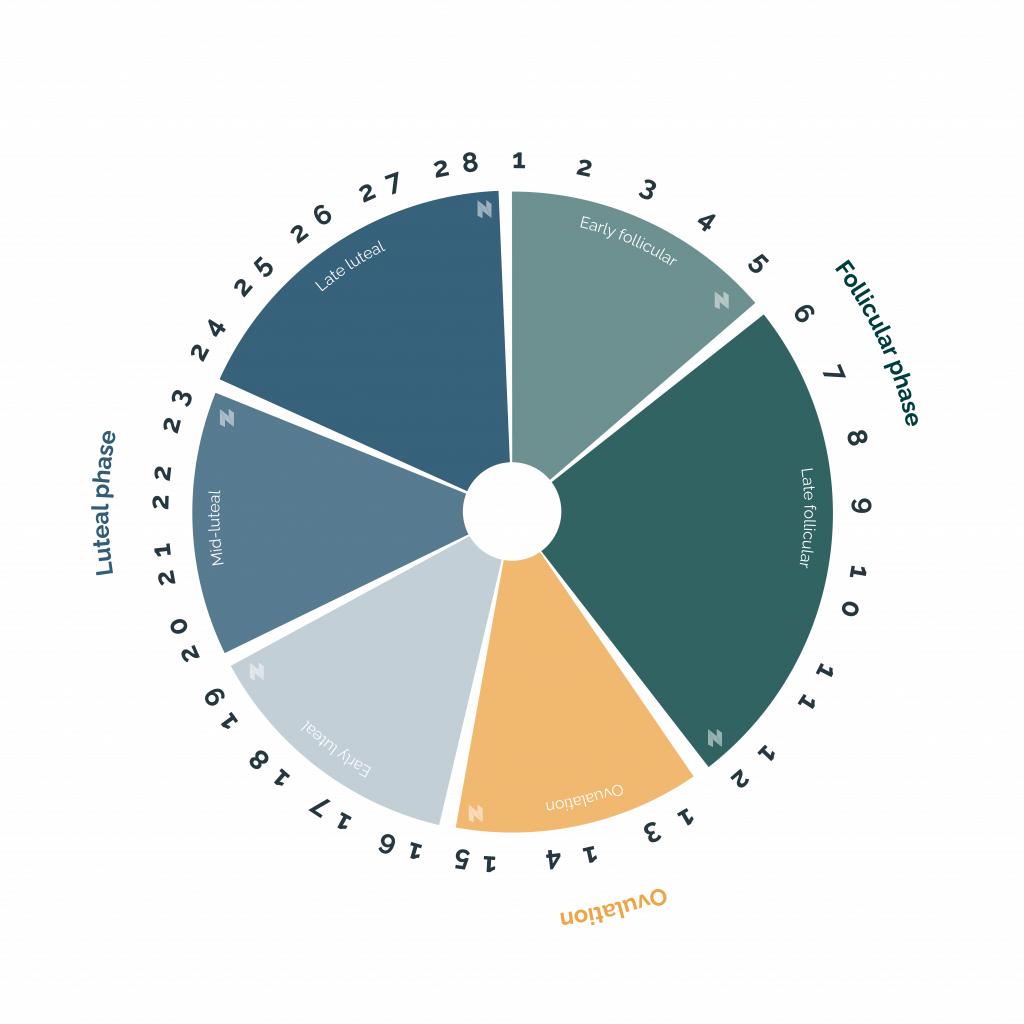

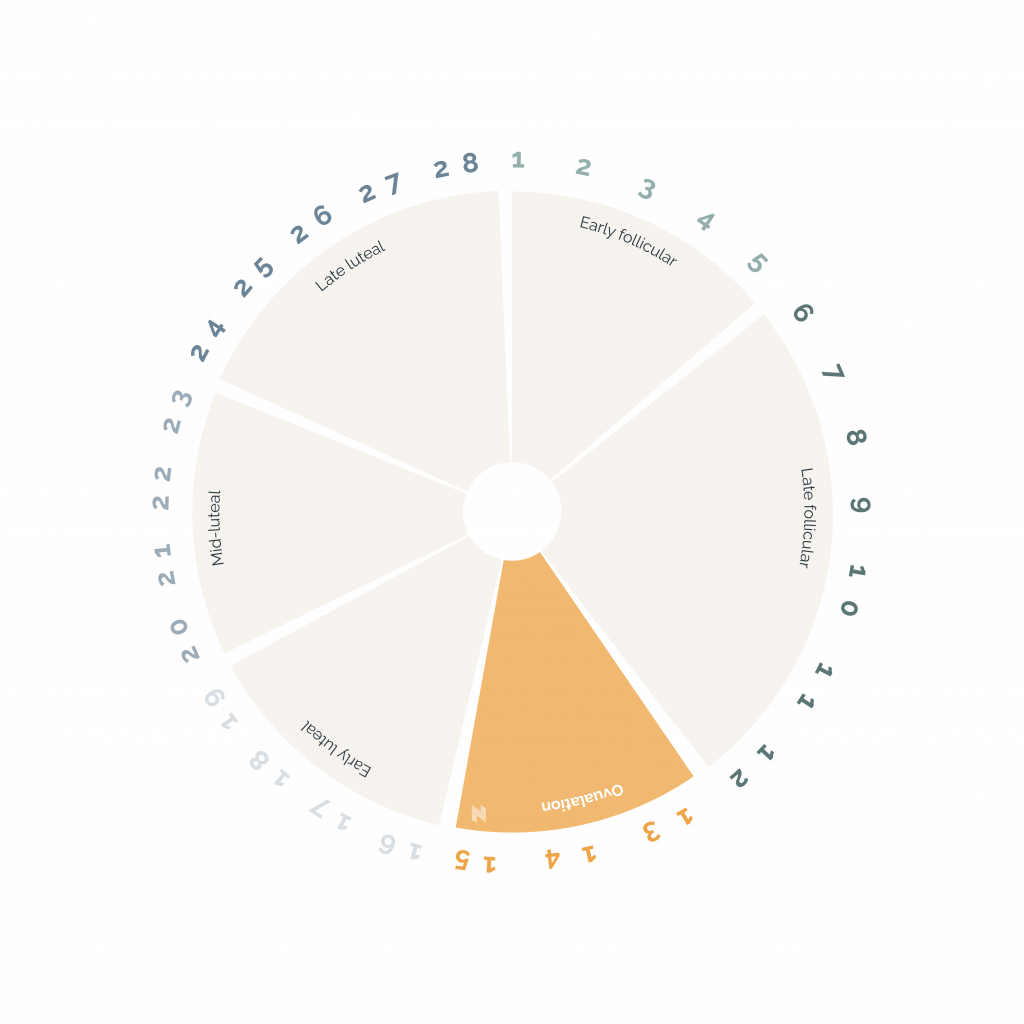

The fairly predictable and measurable fluctuations of the MC allow us to divide the cycle into three different phases: (1) follicular phase, (2) ovulation and (3) the luteal phase.

The follicular phase – can be divided to early and late follicular phase

When: First day of the period until ovulation – usually 13-14 days.

Hormone concentrations: Low oestrogen and progesterone (early follicular phase) and low progesterone and raising oestrogen (late follicular phase).

What: The early follicular phase is the time when menstruation occurs and typically lasts 3-5 days. During that time the lining of the uterus sheds (if no pregnancy is present). During the late follicular the raising oestrogen levels cause the lining of the uterus to grow and thicken. Follicle-stimulating hormone, a different hormone, also promotes the growth of follicles in the ovaries. One of the growing follicles will develop into a mature egg (ovum) between days 10 and 14.

Ovulation

When: about day 14 in a 28-day MC

Hormone concentration: high oestrogen and low progesterone. The ovary releases an egg when there is a sudden rise in another hormone called luteinizing hormone.

What: The ovary releases its egg.

Luteal phase – can be divided to early, mid, and late luteal phase

When: about day 15 to day 28 in a 28-day MC

Hormone concentration: early luteal- low oestrogen and progesterone, mid luteal- high oestrogen and progesterone, late luteal- oestrogen and progesterone are dropping.

What: The egg exits the ovary and travels to the uterus (through the fallopian tubes). To prepare the uterine lining for pregnancy, progesterone levels increase. If the egg is fertilized and attached to the uterine wall (implantation), pregnancy occurs. In the absence of pregnancy, oestrogen and progesterone levels fall, and the uterus’ thick lining sheds during menstruation. The dropping hormone levels are thought to trigger premenstrual syndrome (PMS) which may result in symptoms such as bloating, headaches and irritability, and depressed mood as well as cognitive symptoms such as difficulties concentrating.

Role of female sex hormones on different functions

Research shows that the fluctuations of female sex hormones affect not only reproductive health but may also affect metabolism, inflammation, body temperature, fluid balance and risk of injury, and other important systems (3). For example, it has been reported that both oestrogen and progesterone impact many tissues including skeletal muscle, cardiovascular system, bone, connective tissues and the central and peripheral nervous system (4).

Oestrogen is thought to promote muscle growth and it has shown to play role in metabolism (2). Progesterone is a key physiological component in the MC and the central nervous system, cardiovascular, and immune system (5). The luteinizing hormone plays an important role in sexual development. Emerging data suggests that luteinizing hormone could also play a role in the central nervous system functioning in aging and female cognition (6). Despite these findings, the evidence on how the MC affects exercise performance is not straightforward.

Exercise and the menstrual cycle

Does exercise performance change based on the menstrual cycle?

While some studies suggest that performance may be different depending on the MC, other studies suggest that no or only slight variations exist. The exact mechanisms on how sex hormones effect exercise still needs to be elucidated and currently there is no agreement on this topic (4). Moreover, the relationship on how they impact exercise remains a subject of ongoing research with its fair share of controversy (4). One study describes the lack of generalizability and the need to individualize interventions since the consequences of the MC phases and their relationship to exercise vary from person to person (4). The study concludes that “average data are probably not relevant and could potentially be misleading”.

Menstruating runners perceive that menstrual bleeding is affecting their performance

A study investigated the prevalence and impact of heavy menstrual bleeding in exercising females where anemia may significantly affect training and performance (8). The study reported that 55 % of female participants undertaking the 2015 London Marathon believed that their MC impacted their training and performance, which was especially true for women reporting heavy menstrual bleeding (8). The study found that heavy bleeding is prevalent in elite athletes (37%), and so is anemia (32 %) (8). However, only a minority (22%) sought a medical advice (8). The study had its limitations in that it was based on self-reported data- a questionnaire, and not biomarkers, physical tests, or finishing time of the marathon, to determine performance. Therefore, the data may be biased. Also, the collected data was only for the specific event runners, so it may not be extrapolated to other populations. Despite the study limitations, it is important to recognize that menstruating people perceive that their performance is impacted during menstruation, a lot of them suffer in silence and more research is needed to understand the impact of heavy menstrual bleeding, as part of MC, and its effect on performance (8).

Performance may be slightly reduced during menstruation

Another study also called attention to the early follicular phase (menstruation) and reduced exercise performance (2). The study pointed out that performance may be slightly reduced during the early follicular phase (menstruation) of the MC when compared to all other MC phases (2). The conclusion was presented in a systematic review and meta-analysis, which is regarded as the “gold standard” in medical evidence. The first step taken by the researchers was to review and synthesize existing literature on the topic of the effect of MC on performance of females. There were 78 individual studies that met their inclusion criteria and provided empirical data on this subject. The researchers were interested in studying healthy females aged 18-40 who had regular MC, were not taking hormonal contraceptives and were free from any menstrual related dysfunctions (2). The researchers then used statistical methods to summarize the findings and make conclusions (2). Unlike the study on marathon runners discussed above, the participants of this study were not athletes.

Three aspects of the study deserve attention. Firstly, the difference in exercise performance among the different phases was very small (2). Secondly, there was no uniform definition on performance among the individual studies. For example, total work done, time to completion, time to exhaustion, mean, peak and ratio outputs, rate of force production and decline, and maximum oxygen uptake were all defined as exercise test performance in the review. Thirdly, the way the MC was tracked was not uniform among the different studies. For example, some studies utilized blood tests, others urinary ovulation detection kits, or the participants self-reported their MC. Even though this meta-analysis is a comprehensive study including 78 individual studies with total of 1193 participants, most of the studies were classified as “low” in quality, so the study results should be interpreted with caution (2). The researchers concluded that “general guidelines on exercise performance across the MC cannot be formed; rather, a personalized approach based on each individual’s response to exercise performance across the MC is recommended” (2).

How to optimize performance based on the menstrual cycle?

Due to the gap in research and inconclusive results of the menstrual cycle, general exercise and performance guidelines cannot unfortunately be issued yet.

Nevertheless, although research may point to only slight variation in performance during the different stages on the MC, people who menstruate feel different throughout their cycle and many perceive that menstrual bleeding negatively impacts their performance (1). Due to the fluctuating sex hormones, a lot of people also report symptoms especially during PMS and during menstruation.

Even though general guidelines on how to modulate exercise cannot be offered at this time, there are some recommendations that could be useful based on the existing research. It is to be acknowledged that every woman is different, and that they may not be applicable to all.

General recommendations

Early stage of the follicular phase

During the early stage of the follicular phase (menstruation) a lot of women are experiencing symptoms such as menstrual cramps, bleeding, stomach ache, back pain, headache, tiredness, psychological symptoms etc (9). Also, as the data suggests, exercise performance is slightly reduced, or perceived as reduced during this time (2,8). One report suggest lower endurance capacity during this stage (10). Therefore, taking it easy but still moving and staying physically active is recommended. Activities such as walking, yoga and mobility training are great choices for this time of the period.

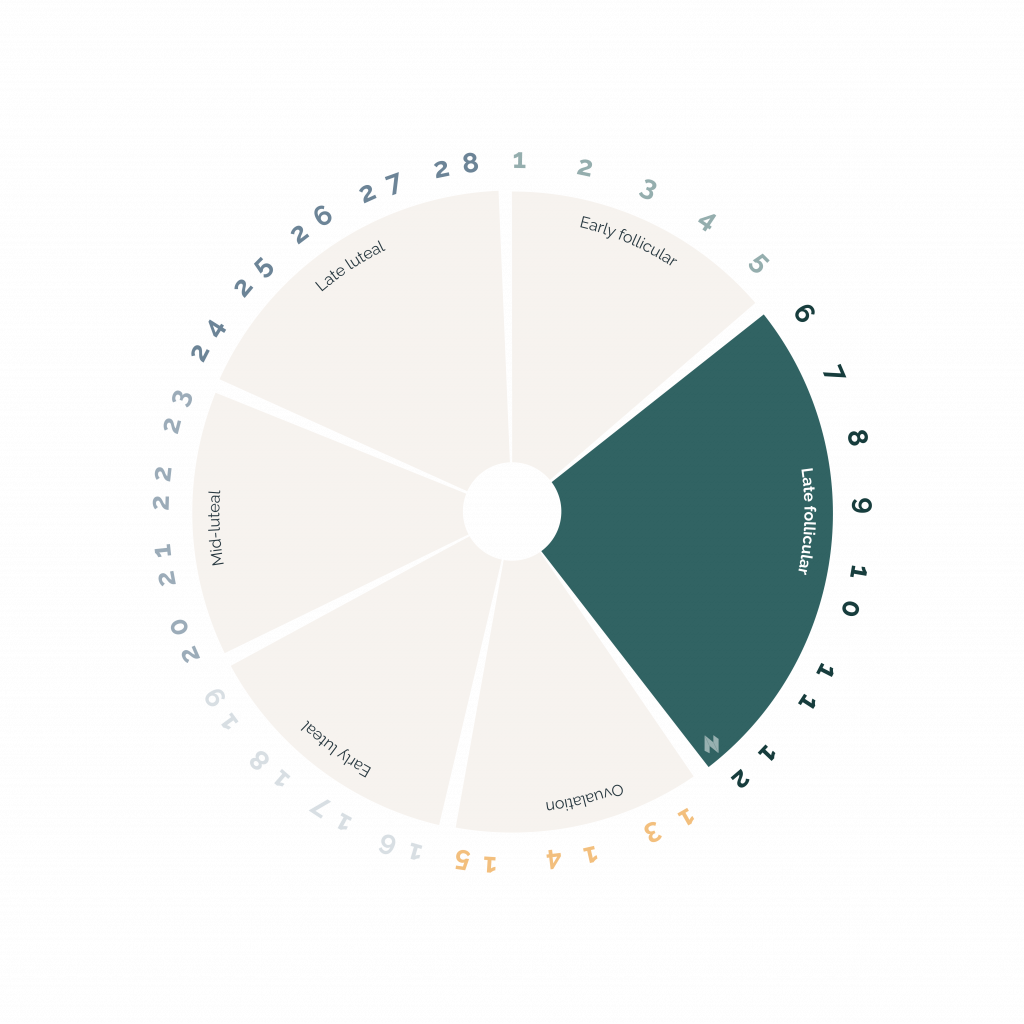

Late follicular phase

During the late follicular phase, progesterone levels are still low, but oestrogen levels are the highest. It is thought that the rise in oestrogen leads to higher ability to build muscle and the body adapts and recovers better (7), (11). Most women feel energized during this time. There is emerging evidence that strength training is most effective during this time, and that the body recovers better (7). Strength training, weightlifting, high intensity workouts and resistance training may be most advantageous during this time (10).

Ovulation

Some studies suggest that there is increase in strength during ovulation compared to the follicular and luteal phases (11). It has been suggested that the surge in oestrogen just prior to ovulation may be responsible for increase in muscle strength. Thus, high intensity workouts and endurance training may also be suitable during ovulation.

Early and mid-luteal phase

Progesterone and oestrogen are elevated during the early and mid-luteal phase. One study suggested that the pre-exercise heart rate was significantly higher during the luteal phase, suggesting that the heart is working slightly faster than normal (10). That suggests that high-intensity workouts are not suitable for this phase. Most women feel good but may not be as fresh and energized as compared to earlier MC phases. Exercising is recommended but adjustment of the length/intensity of the routine is suggested with plenty of recovery time in-between training sessions.

Late luteal phase

During the late luteal phase many women experience PMS symptoms such as excess water gain, bloating, fatigue and lack of energy. Although research may suggest that the performance may not be affected, it is recommended for women to listen to their bodies and to adjust their exercise routines to their level of comfort. Tracking of symptoms and exercise performance during the MC can give additional insights on the unique patterns and lead to increased self-awareness.

Finally, one point to mention is that the MC is highly individual, and understanding the MC and listening to one’s body may be the best approach to optimizing exercise routines. Moreover, exercising is recommended in any phase of the MC as the benefits of exercise are well established to improve the well-being. Due to lack of robust evidence, a personalized and patient-centric approach is needed.

References

1. Bruinvels G, Burden RJ, McGregor AJ, Ackerman KE, Dooley M, Richards T, et al. Sport, exercise and the menstrual cycle: where is the research? Br J Sports Med. 2017 Mar 1;51(6):487–8.

2. McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E, Swinton PA, Ansdell P, Goodall S, et al. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med Auckl Nz. 2020;50(10):1813–27.

3. Oosthuyse T, Bosch AN. The Effect of the Menstrual Cycle on Exercise Metabolism. Sports Med. 2010 Mar 1;40(3):207–27.

4. Rocha-Rodrigues S, Sousa M, Lourenço Reis P, Leão C, Cardoso-Marinho B, Massada M, et al. Bidirectional Interactions between the Menstrual Cycle, Exercise Training, and Macronutrient Intake in Women: A Review. Nutrients. 2021 Feb;13(2):438.

5. Nagy B, Szekeres-Barthó J, Kovács GL, Sulyok E, Farkas B, Várnagy Á, et al. Key to Life: Physiological Role and Clinical Implications of Progesterone. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jan;22(20):11039.

6. Mey M, Bhatta S, Casadesus G. Chapter Five – Luteinizing hormone and the aging brain. In: Litwack G, editor. Vitamins and Hormones [Internet]. Academic Press; 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 4]. p. 89–104. (Hormones and Aging; vol. 115). Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0083672920300534

7. Oleka CT. Use of the Menstrual Cycle to Enhance Female Sports Performance and Decrease Sports-Related Injury. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020 Apr 1;33(2):110–1.

8. Bruinvels G, Burden R, Brown N, Richards T, Pedlar C. The Prevalence and Impact of Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (Menorrhagia) in Elite and Non-Elite Athletes. PLOS ONE. 2016 Feb 22;11(2):e0149881.

9. Schoep ME, Adang EMM, Maas JWM, Bie BD, Aarts JWM, Nieboer TE. Productivity loss due to menstruation-related symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional survey among 32 748 women. BMJ Open. 2019 Jun 1;9(6):e026186.

10. Bandyopadhyay A, Dalui R. Endurance capacity and cardiorespiratory responses in sedentary females during different phases of menstrual cycle. Kathmandu Univ Med J KUMJ. 2012;10(40):25–9.

11. Sarwar R, Niclos BB, Rutherford OM. Changes in muscle strength, relaxation rate and fatiguability during the human menstrual cycle. J Physiol. 1996;493(1):267–72.